This is the first in a series I’m calling “Object History” wherein I try and put cultural detritus into context. Fun fact: “Detritus” in the biological sense describes what is left over during active decomposition.

In the next several installments, you’ll find an account of the literal and figurative journeys associated with some rare (if not particularly valuable) writing instruments. Along the way I investigate a long-dead stranger, nearly stalk his nonagenarian daughters, contend with permanence in a disposable culture, and make the acquaintance of a man who was at ground zero of a retail sea change. The story ends with two old men bragging about their kids in family law. It starts at the funeral of a 19th-century indigent, mummified by mistake not long after Joseph Dixon (of Dixon-Ticonderoga fame) got into the pencil business.

Cultural Detritus

Pure chance put me in the aisles of the biggest antique mall in Adamstown, Pennsylvania, the antiques capital of the U.S. Kelly and I came to the region to cover a peculiar funeral in October 2023, the interment of a 150-year-old American mummy. You can see the story of Stoneman Willie, his botched embalming and rise to town mascot here, but the upshot is we treated ourselves to a day’s worth of antiquing as an early anniversary present. Hunting in junk and antique shops is a hobby and mild obsession we’ve cultivated together.

In Reading and the surrounding area, it’s easy to see glimmers of the region’s former greatness among the tatters of American manufacturing. We stayed, for instance, in the repurposed home of a plumbing magnate who, with two of his brothers had built three townhouses in a row. One burned down (at some point) and some 21st century owner diced the others into about a dozen railroad apartments.

Coming down the left half of what at one time must have been a grand staircase, we tried to imagine the home in its heyday, when the foyer didn’t smell of pot and the front door still locked. Except for the creeping concern that the facility seemed two rainy seasons away from developing a serious mold problem, you could see the potential. Ours was the only Airbnb apartment, and there was a sense the home and neighborhood were on the verge of a comeback.

The townhouse was one of several substantial homes in a neighborhood ripe for gentrification, a clean-shaven former addict, looking a little rumpled but optimistic about his first day of work. There had been a nearby gunshot our first night there, so whether and how well the neighborhood will turn out remains very much up in the air.

Not quite 20 minutes away in Adamstown, the transition feels a little more complete. Except for the employee-owned Bollman Hat Company, which recently celebrated its 155th anniversary, the “antiques” industry appears to be the town’s primary economic engine, with an astounding number of quirky, dusty stores and at least one massive antique mall.

The City of Lost Wealth

It didn’t take much imagination to see Adamstown in a dystopian light, run by a scavenger/merchant class that dealt in repurposing whatever they salvaged from the failing estates over the years. If “Reading” didn’t ring a bell for you, think “Monopoly.” A hundred years ago, the entire region was flush with railroad cash and teeming with entrepreneurs hoping to capitalize, literally and figuratively.

Over time, fortunes change, people die intestate, and economies collapse and rebuild, creating surplus luxury items that find their way into the repurposing economy. Items pawned or sold at estate sales shake out into the waiting arms of local dealers who repackage them as antiques for tourists like Kelly and me to gawk at and Instagram.

Some call it “thrifting” and others “antiquing” but I’m doing something different. I’m collecting stories, not looking for deals. Many of the stories I find are nostalgia driven, reviving forgotten anecdotes about toys or games I used to own, or housewares or decorations I remember. What interests me most are relics I can look into and learn from.

Every item at any second-hand store doesn’t just have a past, it has an origin story, a day it went from possession to commodity. I am so interested in that transition, that moment someone decided they didn’t want an item and would rather sell it than trash or donate it.

Coming from a culture of “find someone who needs it or donate it,” I don’t know if I’ve sold anything in my life. It just feels like a hassle in a world where people either need or want stuff I no longer do. That’s not to throw shade at people who get great pleasure in the hunting and trading of used (collectible?) wares. Turning a profit on garbage is the American way, after all. Nostalgia exists in a permanent bull market, but we’re still dealing in detritus, sifting through the remains of better days.

That’s what makes the antiquing project a little sad, especially when we’re talking about an industry that has evolved from essentially pawn brokering. Walking through row after row of old toys, forgotten fads, and Oriental offerings of dubious provenance, I thought of the estate sales that filled and continue to fill these stores. How many of these antique boot scrapers were from liquidations held at the grand homes in my Airbnb’s neighborhood?

Anthropologically, it’s, like, “These are the things we think our wealthy people thought were worth having.”

I’m not an anthropologist, though, I’m a story junkie and want to know origin details. Sometimes they’re short, sad, and to the point, i.e., once upon a time, a middle-aged woman made owning Elvis memorabilia her whole personality. Now she’s dead and all that’s left is a quandary of value for her kids over a pile of garbage that their mom treasured.

I saw a story like that unfold in Adamstown. For people who live there, selling heirlooms to one of the dozens of antique dealers must be more appealing than just hauling mom’s junk down to the GoodWill. It’s not about what we treasure, but what we can get for what we treasure.

The Eye of the Beholder

“I’m telling you. I would offend you if I made an offer,” an older man was saying. His tone, soft but direct, as if he wished with all his soul he had better news, caught my attention as much as his words.

The woman he addressed looked to be in her 40s and was smoker-skinny. She spoke in a drawly, Pennsyltucky accent at the crossroads of Mid-Atlantic and Midwest. She’d tucked her fading blonde hair behind her ears, brushing the golden tips back and over her shoulders, swinging behind, a few strands catching on her brown turtleneck.

One bony hand rested on a shopping cart filled with boxes of Precious Moments figurines, the other provided emphasis as she explained her situation. She didn’t want to “just” throw the figurines out; they were her mother’s after all.

The vendor spoke her language literally and metaphorically. Pushing 70, with substantial plastic-framed glasses and the last of his dancing across his scalp to the shaggy fringe, he wasn’t quite stooped, but his shoulders pulled themselves forward a bit in his blue-and-red-stripped Oxford so when he shrugged he also appeared to lurch.

“I know people collect these but they’re not as valuable as they think,” he elaborated about the market and the difference between what something costs in a shop and its resale value.

You could see the wind come out of her, followed by a small chiding for her premature enthusiasm. This was not a woman who got breaks in life and (I think) at some level she must have known she was throwing a Hail Mary on selling her mother’s Hummels.

She might move the collection a piece at a time on eBay if she wanted to make the effort, but her face said she’d already spent cash she’d convinced herself was her due, birthright, and inheritance.

The vendor would not go through her collection and individually value each piece and explained that it would take a while to sell these (if they sold at all) causing a storage problem. Again, you could tell the guy felt bad. This woman had a hard go of it long before losing her mother. That doesn’t mean he wasn’t resolute, only that he was a man used to crushing hopes as gently as possible. I could tell he had no interest in storing her tchotchkes at any price.

It takes a special mix of faith and desperation to walk into a junk store cold, intent on selling a shopping cart worth of trinkets to a single dealer. The vendor offered light condolences, shaking his head in a “whataya gonna do?” attitude, as the woman suggested that she would rather take less than lug these all back home.

I’m sorry to report she was still angling for some sort of ballpark valuation when I passed out of earshot with no sufficient excuse to linger. This vignette played out in an abandoned section of the antiques mall, so there was no place to pretend to browse while I eavesdropped. Plus, I was still a little high from having scored an antique coup of my own moments before.

“The Acme of Writing Perfection”

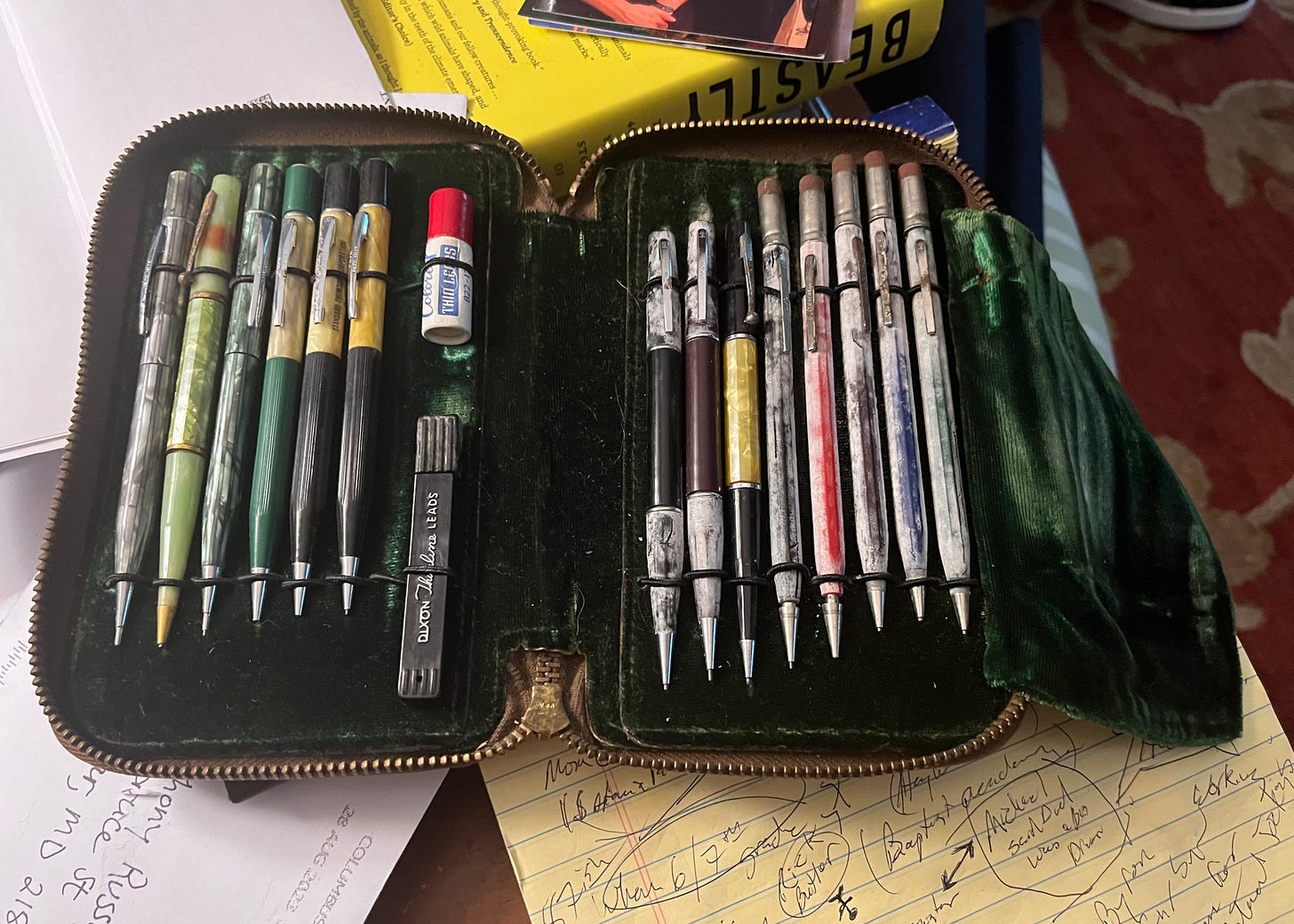

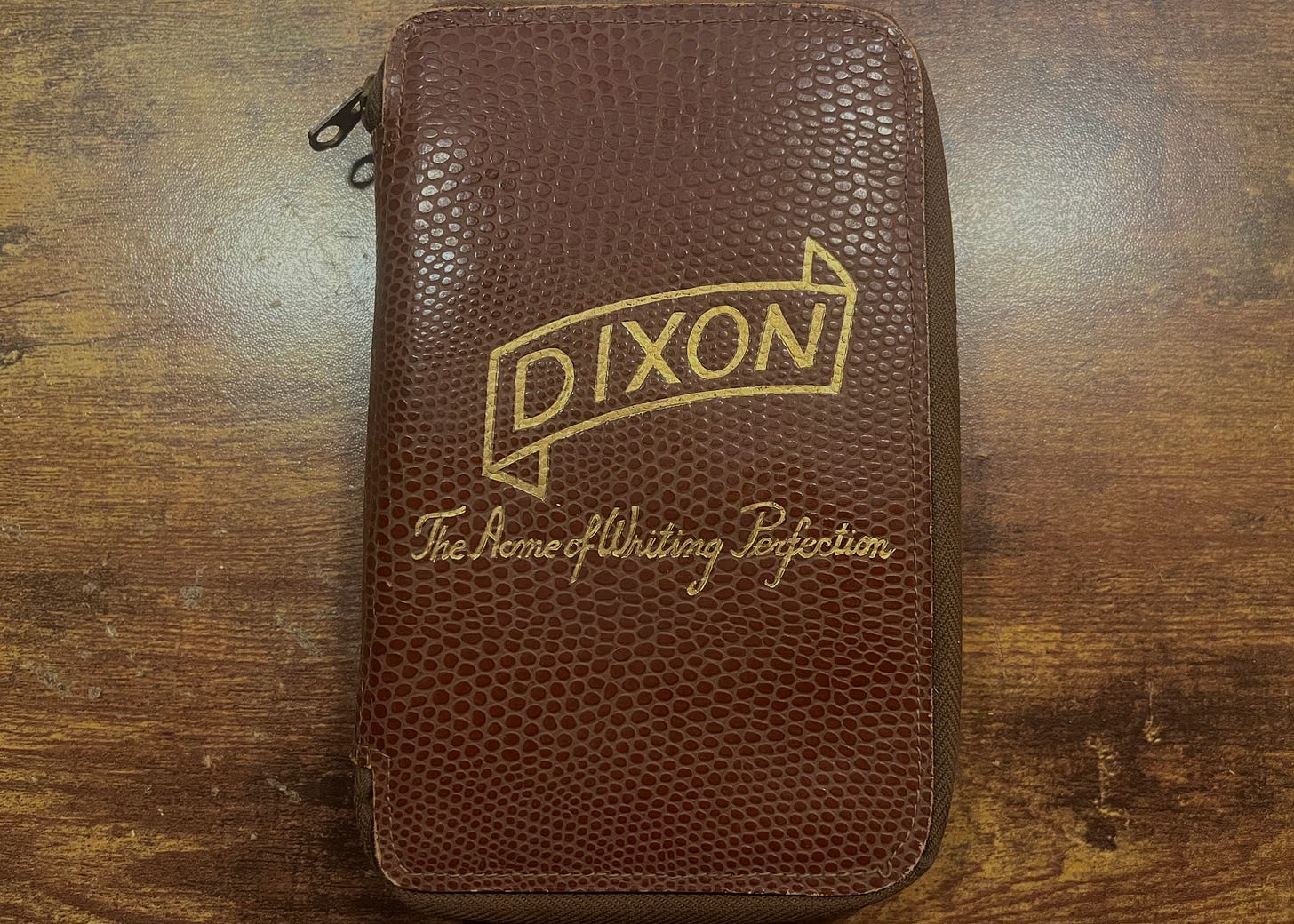

Around the corner, Kelly had found a mechanical pencil set and case sitting open on a planter delineating a stall. The pencils (there were 14 but room for 16) came inside a brown leather portfolio lined in green velvet about as wide as a paperback book and maybe three inches taller. Two lead refill containers, red and black, respectively were shoved into pencil slots. The front said “Dixon” and, in smaller type, “The Acme of Writing Perfection” embossed in gold on the front.

Although I didn’t like them as much as the person who was selling them thought I should—the pencils spoke to me. I was lucky. The dealer wasn’t around, so I had time to consider whether I wanted to make an offer and what this collection of pens was worth to me.

After 10 minutes of waiting for the vendor to return, I wandered down the aisle a bit and loitered just outside a conversation two other vendors (pudgy white guys from flea market central casting) were having. One wore a reproduction Pink Floyd tee and dealt in vintage toys, the other (in a black and white Tommy Bahama) dealt in vintage records.

One day I’ll return to Adamstown and write about the vendor culture and all its colorful characters. All seemed to have friends and frenemies among their colleagues. I cannot begin to imagine the petty intrigues, but I would love to hear them told: who’s a thief, who’s a patsy. In a community of narrow niche experts, the egos must be spectacular.

I broke into a lull in a conversation about the relative merit of working known slow weekends to ask if either ran the stall across the aisle as well. Tommy Bahama looked at me from under his tan ball cap and confessed he was watching the store.

I offered him $30 for the $60 pencil set. Half-off must have been above his pay grade because he called the proper owner to check. I’m no haggler and as the phone rang, I resolved $30 was my final offer.

My stomach tightened as I prepared to walk away rather than dicker over $5, but it was wasted anxiety as the owner agreed in seconds. Then I felt taken advantage of and (and this is uncharacteristic of me), tried to find a similar one online to get a sense of the “real” price. I was wandering around trying to get signal when I happened upon the Hummel negotiation and resolved to continue my research at home.

Back in Delmar, I spent two days scouring the internet, launching myself into the collectible mechanical pencil world (which is a real place with real and very passionate residents).

The research filled my head with the Dixon-Ticonderoga pencil company facts, including that it started as a crucible manufacturer selling pencils on the side with extra graphite. During the Civil War, pencils caught on among the soldiery, being easier to write home with than ink pens. When you see those “My Dearest Martha,” Civil War letters, know they’re written in Dixon pencil.

Many of the pencils in the case fetched $10-$20 on their own, but I came to a complete and utter dead end on the pencil case. A year on, I’m no closer to discovering anything about this pencil case, or even finding another one (which seems inherently unfair given how much stuff is on the internet).

A strange, chalky-white patina known to collect on older pencils, or pieces of bakelite (or whatever protoplastic these were made of) marred the collection. Dave of Blogger site Dave’s Mechanical Pencils told me as much after I emailed him. The site hadn’t been updated in more than a year, but he answered immediately telling me the schmutz should come off with a credit card. When it did, I told him as much and closed my thank-you note thusly:

“Anyway, I’ll remain vigilant and hopefully rehab them. I may even start a collection now that I’ve been reading your site.”

Usually, when I reach out to strangers it’s because they were involved in something horrible and I want them to tell me about it. This time, I was just connecting for information, but the entire experience—searching for information on Dixon and learning that there was a near-fanatical collector community—gave me another way to approach stories.

For the last few months, I’ve been looking into another origin story, not too dissimilar from the Dixon pencil case. It’s the story of a pencil set from a company that isn’t only defunct but may have never existed.

I’ve been poking around, collecting evidence about these pens for so long it’s become something of a driving mystery I’m aching to solve. As I write this I’m following my final lead. I’m very close to either a spectacular revelation or an Al Capone vault moment. Only time will tell.

Next: “A Writing Implement of Distinction”