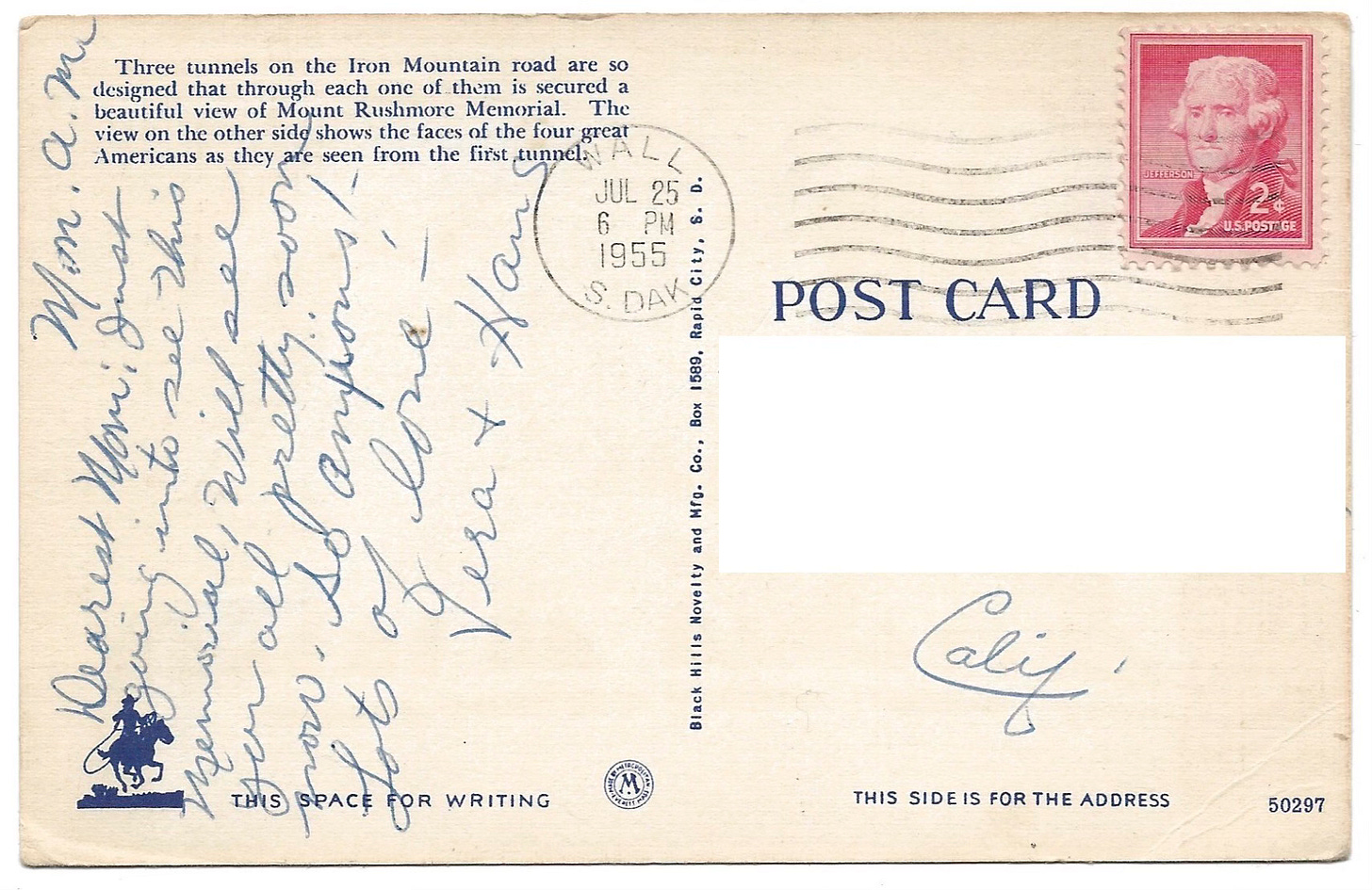

On Monday, July 25, 1955, Vera and Hans (a pair of road-trippers) sent a postcard from Wall, South Dakota, to San Fernando, California. It said this:

“Mon. a.m. Dearest Mom: Just going into see this memorial, will see you all pretty soon now. So anxious! Lots of love — Vera + Hans”

This is the story of that postcard, or as much of it as I can figure.

Visiting Wall Drug: A Personal History

The speedometer said 100 as the Dodge Ram we’d rented ate up Rt. 90, bouncing gently with the otherwise imperceptible rises in the highway like a speedboat clipping the waves, but the peaks and valleys were subtler, as if someone were jumping up and down on the back bumper. I was speeding for speeding’s sake and marveling at the endless road ahead. You could go 60 or 80 or 120 and the mountains were no closer. Their distance was measured in days not hours.

Imagining what the trip must have been like on a mule or wagon train, how hot and hard and slow, I was grateful to know that there would be a Love’s or TravelCenters of America with their huge well-lit signs and well-appointed toilet facilities every 90 minutes, that even if I broke down without cell service, someone would come along with help, at least in the daytime.

Driving after sunset on a moonless prairie night is like sitting in a closet; I can see only as far as the end of my headlights. At night I dial way back on the speed and let myself be a little mesmerized by the clusters of towns off in the distance, pockets of light in the vast plains dark.

Even if those towns were there 100 years ago, the lights probably weren’t, and traveling in the dark was way dumber than driving 100 miles per hour. I imagine the sick feeling of hearing the engine cough, or seeing those first clouds of vapor seep through the hood with only a vague idea how far it was to (or since) the last town.

Whenever I make the cross-country drive I’m awestruck by the American West’s simple beauty and terrible emptiness. The buttes don’t care whether you live or die and more than do the sage brushes. The faux romanticism of unspoiled America is an easy trap to fall into when you can drive for so long between McDonald’s drive-thrus, but they’re there, waiting like Secret Service Agents to save us from the realities of the “Old West.”

Still, as someone for whom the ocean has always conjured the midway rather than the beach, I was happy to be lulled into the unspoiled America narrative and, as a result, a little grossed out by Wall Drug. I want to call it the “South of the Border” of the West, but that doesn’t get at the former’s all-encompassing nature. Where South of the Border is a trinket shop that mutated into a low-rent amusement park. Wall Drug is a straight business that mutated into a town. I feel like there’s an East Coast West Coast comparison, sentimental kitsch versus garish nostalgia, but as with the fundamental difference between South Beach and the Vegas Strip, there’s a kinship as well. A through line.

We’d spent the previous two nights in Sioux City, Iowa, a hellish berg where the Great Depression is alive and well. It’s a story for another time, but suffice it to say we were up and out early and well ahead of schedule.

I don’t believe you can drive 10 minutes without seeing a Wall Drugs sign for 300 miles in any direction, which is likely what conjured “South of the Border” in my mind. In my research, I discovered that the comical number and nature of the signs started out as a joke that spun out of control. The founder stumbled across some scrap wood well outside of town, painted “Wall Drug” on it (he happened to have paint and brushes handy), and propped the “sign” on a scraggly tree. Every time he added a sign, business increased, so he kept adding signs.

It was approaching noon and Wall Drug already was a madhouse as I dropped Kelly and went to find a place to park. In another connection to East Coast beach resorts street parking is fictional in Wall, South Dakota. Fortunately, this is the West and they have enough space to encircle the town with a parking lot; it was as if Wal*Mart got its Pinocchio wish and became a real live municipality.

Garish nostalgia and sentimental kitsch, it occurs to me, are bound by cynicism, which is all that’s left when the novelty fades from commerce. Just as with the Jersey Shore, or closer to home for me now, Ocean City, it’s not any town’s fault that it’s a tourist trap. After decades of trying to live up to nostalgia, the effort has to collapse under the weight of unsupportable expectations. Things aren’t like they used to be because they never were that way. Sometimes things become caricatures, sometimes they become cartoons.

Ambling along the boardwalk connecting the various shops with their tacky keychains, bawdy tee shirts and chintzy reproductions, I could have been on the any boardwalk in the East. It was July 2021, and even though I was vaxed and masked, I could feel the pathogens in the air, imagine them in clouds around the people exasperated by my virtue-signaling.

I’d under-packed and needed a sweatshirt for the unexpectedly chilly high plains evenings. The store was shoulder to shoulder, kids leaking snot over their filthy lollipop mouths, grownups in commemorative tee shirts making performative and impotent threats, and me, who hadn’t been in a room with more than two other people in it for nearly two years.

Claustrophobia set in hard and I decided I’d rather freeze than be inside queuing with the unwashed to pay $60 for a hoodie proclaiming I’d visited Wall Drug. Kelly, who as a teacher was able to function in the post-social distance chaos, insisted she would stay and get the sweatshirts (she even found me an unbranded one) while I retreated to the safety of the truck like a man and walked the dog.

All in all, we spent less than an hour at Wall Drug, and it mostly had faded from my memory by the time we set up camp in the Yellowstone KOA in Custer, South Dakota.

Even today, given that I’ve discovered a reason to remember it, the memory is illusive, like a dream about being trapped in an Ikea-sized Bob Evans. The idea that I would be grasping for Wall Drug details three years later because of a 70-year-old postcard I came across would have seemed preposterous. I mean, it is preposterous, but here goes.

Wall Drug Revisited

A lot of times I think we have commerce backward. We complain about corporate greed as if we aren’t participants, balls of indiscriminate want clamoring for lower prices. We built Wal*Mart (and Wall Drug) into what they are today, reflections of our bottomless need.

When Ted Hustead bought Wall Drug in 1931, his plan wasn’t to turn the vast Dakota wilderness into a cheap Wild West sideshow, his plan was not to go broke out in the middle of nowhere during the leanest decade of the Great Depression.

According to the company website (which is totally worth the visit), Hustead sought an apothecary in a small town that had a doctor (to write prescriptions) and a Catholic Church (he and his wife Dorothy were daily attendees). Wall fit the bill, and even though his family complained that it was in the middle of nowhere even for 1930s South Dakota, the Husteads staked their claim in the town of 326 souls.

By 1936 they were ready to quit. They were barely scraping by with prescriptions and the few advertising efforts they made seemed to fall flat. Dorothy had a pitch that summer: put a sign out on the highway saying “Free Ice Water.”

This is the part where I wish I had the power to evoke the nothingness for miles and try to find a way to get you to amplify it, to imagine the 1930s roads stretching so far into the unbroken distance that it seems two-dimensional, like a child’s perspective drawing.

Given the vast nothing preceding it (Sioux City was a six-hour drive), even for the skeptical, the words “Free Ice Water” must have been a huge draw for people driving cars without cup-holders.

By the time Vera and Hans mailed their postcard, Wall had more than tripled in size and become as much a roadside attraction as a drugstore/soda fountain. People started wanting hot food to go with their Free Ice Water and souvenirs of the American West to prove they were there, and, of course, postcards and a place from which to mail them.

Wall may have been in the middle of nowhere in 1931, but in 1941 the opening of Mount Rushmore transformed Wall. If you’re coming to the national monument from points east, you’re passing Wall Drug. An accident of history (or geography) transformed Wall from an emergency stopover to a roadside attraction.

Wall Drug Pre-Visited

The postcard looks to have been made from a hand-colored photo of Mt. Rushmore taken at the mouth of a tunnel that opens up to the monument. I noted the postcard was licensed by the Black Hills Novelty Company, half-an-hour north in Rapid City, Iowa (and discovered a specialty postcard printer printed it in Massachusetts). Carving up that mountain didn’t just help kick-start American road tripping, everyone suddenly had a new revenue stream.

I don’t know if Vera and Hans bought the postcard at Wall Drug, but I think they must have because they were California bound. When I talked before about having trouble imagining this trip in the past, they were the couple I had in mind: 1950s-young adults, aged by privation and cigarettes.

As much as we (probably rightfully) romanticize the Great American Road Trip, only something like 30% of cars had air conditioning in the 1950s. There’s a two in three chance that Vera and Hans drove across the American Plains with the windows down. By the time they hit Wall Drug, the dust must have been incredible and the Free Ice Water must have tasted like candy.

Since back then the cars weren’t as aerodynamic, with the wing open you might hold some conversation. While it’s possible that you could have gotten the occasional radio signal out there, in all likelihood the trip across the plains and down through the desert was all searing heat and howling wind between gas stations. Wall Drug must have looked as much like a mirage as an oasis.

Another cool factoid from the company website: during one of the many expansions, the building ran up against an old tree and Dorothy whose “Free Ice Water” plan had been a multi-million dollar idea, told her sons to build around it, so they did. They also erected a sign that said, “Eat Under the Tree.”

https://www.walldrug.com/assets/images/uploads/old-wall-drug-photo-scan.jpg

According to the postcard, Vera (I like to think it’s Vera rather than Hans) wrote her mom a note in the morning, but it wasn’t posted until that evening. My guess is she missed the morning mail.

Several postcards in this ebay-purchased batch not only have morning dates but also contain promises to write again that evening. They’re usually addressed within the same (big) city and designated a.m. and p.m. by the authors. Maybe Vera and Hans are from a city and marked the time as a matter of habit. I honestly can’t imagine that Wall, South Dakota, was shipping out mail twice per day.

As interesting as the trip behind them may have been, we know the trip ahead of them following their leisurely ride away from Mt. Rushmore and down Iron Mountain Road was arduous at best. Vera and Hans must have been from a northern midwestern state, if not Minnesota (a lot of postcards in this batch were Minnesota-themed), maybe Ohio, for this route to make much sense.

I guess if it’s a once-in-a-lifetime trip a visit to Mount Rushmore is inevitable, but the route from the monument to San Fernando seems unnecessarily brutal if they started even as far south as Chicago, from there the sanest route takes travelers south around the Rocky Mountans.

As Vera and Hans set out from Wall that July morning, it was probably in the low 70s. The temperature would approach a pleasant 90 that day, as the trees and altitude provided some relief. Winding up over Iron Mountain Road, the rock formations and little secret-looking open enclaves in all their beauty and mystery were the real sights to be seen.

There was no magic at Mount Rushmore, though. It looked pretend in the way I imagine the Empire State Building might seem to a tourist, more movie-prop than feat of human engineering. The treasure was the view into the distance it allowed, demonstrating that the real feat of human engineering was the fact that we carved any civilization out of this vast wilderness at all.

As with Vera and Hans, Kelly and I stopped at Mt. Rushmore on our way West but we didn’t stay or picnic. We went only as far as the parking lot, satisfied that the selfies from there would be sufficient proof we made the pilgrimage, then continued down the mountain opposite of the way we came and returned to Custer and some truly uninspired craft beer at the Mount Rushmore Brewery.

I’ll admit to having a dim view of tourist destinations before the pandemic. After all, you can’t have a mob mentality without a mob. On this trip, though, drinking a homebrewy-amber ale, amid aggressively outdoorsy vacationing helicopter parents, it was something else; a Make America Great Again inkling tied to how sanitized trekking into the American Wilderness has become.

Somehow the crowds packed around Yellowstone amplified an essential human cowardice. For all our claims of treasuring freedom and independence, we herd comfortably around easy food and the protection of the pack. We want to connect with nature, but not on its own terms. In tourist towns all across the West we’ve transformed the wilderness into some weird nature zoo.

Of course, strictly speaking we always have to connect with nature on its own terms. We’re in it and part of it. Technology is our evolutionary advantage and there’s nothing more natural than using it. Our evolutionary success is also our fatal flaw.

What’s romantic about Vera and Hans’ trip is that they made it for fun and mostly on their own. Middle class road trip vacations were still brand new at the time. If Hans was driving, then Vera was on the map, checking for signs that assured them they were on the correct highway and not speeding off into the greater unknown.

Even they must have marveled at the settlers, though, and understood how desperately they were counting on shelter and being welcome at each gas station, on a friendly face should their car overheat. I’ll go out on a limb and say the odds are pretty good that Vera and Hans were caucasian. By the 1950s, America was officially a land where help wasn’t too far away if you were white and could see blacktop. Tourists then at least got to play pioneer, setting out into the reduced-threat wilderness while telling themselves that “reduced-threat” isn’t “no threat” which, if you think about it, is “some threat.”

Still, I have to admire Vera and Hans. Maybe unlike Kelly and I, they did picnic at Mount Rushmore before continuing south to California. The drive today, diagonally through Wyoming and Utah maximizing their time in those desolate places, takes about 20 hours. Even if they’re young and driving a brand new car made from the finest American steel, that’s probably a three day trip over pre-Eisenhower Interstate roads.

They must have been eager to get off the road, but they also had to pass through Las Vegas with only five hours left in their drive. I can’t imagine they didn’t stay the night, even if they weren’t gamblers and arrived at Vera’s sister’s just in time for lunch the following day. I like to think she served them tuna but I don’t know why.

There’s nothing like a road trip. It’s so quintessentially American, highlighting the highs and lows of whatever counts as our national dispositions.

This morning I returned the letter to the address that originally had been on it. The letter was posted 69 years ago, so I don’t hold out a lot of hope of finding Vera or Hans, but maybe I can get a bead on their family. I’m certain they spoke fondly of that trip for the rest of their lives. Maybe like me they remember being underwhelmed by Mount Rushmore but forever changed by driving late in the desert dark, marveling at the depth of the black and the vast of the unknown beyond.

PostScript

As too often happens I pulled the wrong thread and spent an hour researching Hustead family history. Jon Hustead died on June 4, 1977, three months past his 21st birthday. He was driving drunk and flipped his vehicle, although that’s not how it was reported at the time. Only the rollover and the fact that the two passengers survived made the paper.

I wonder how common that was in the 70s. I feel like it probably was pretty common. This story reports that Hustead’s wasn’t even the only “rollover” pickup death that evening. The first mention of alcohol I could find was in a story about his State Trooper brother-in-law who uses Jon’s death as a cautionary tale at high schools.

I felt somehow compelled to find out whether he was sober or not when he died. Whenever I see a sickeningly short interval between the “Born” and “Died” I obsess over the cause of death. I don’t know why.

I mean, whatever age I am is always going to be too young to die, but you see some ages and know it is somehow extra tragic. I honestly always hope to find out it’s a disease. I think that’s why I look. I don’t know why I secretly root for illness. It’s not as if it’s any less tragic than other forms of incredibly bad luck that can take a young life. It’s superstitious.

Bill Hustead, the young man’s father and CEO pharmacist at Wall Drug during its massive growth phase, was a state senator. One of the things he’s known for, listed among his accomplishments in the South Dakota Hall of Fame, is finding a way around federal legislation that would have limited roadsigns along federal highways.

If that’s not American altruism what is? I hope to Christ they put up a statue of him fighting for the rights of all free Americans to defend their personal fortune by buying themselves a seat a the table.